"Keeping History Alive..."

- David Grassé

- Apr 14, 2021

- 4 min read

Earlier today, April 14th, 2021, the Hashknife Pony Express came riding into Payson to deliver the mail, just as they do every year (albeit, usually in January). Their journey begins in Holbrook, and these horsemen travel about 200 miles to the city of Scottsdale, carrying about 20,000 pieces of first class mail along with them, (all with the blessing of the United States Postal Service). En route, the riders pass through the towns of Overgaard, Pine, Heber, Fountain Hills, and, of course, Payson. At most of these places, a small crowd – predominantly family groups with small children - will turn out to see the riders and their horses, take photographs, and have their letters picked up.

This annual ride is presented by the members of the Navajo County Hashknife Sheriff's Posse, a group of older, affluent gentlemen (affluent enough to afford the horses, the trucks and trailers, and the many other accoutrements that go with owning a luxury animal). Many of these riders have a background in either law enforcement or the military. The organization even has a military-like hierarchy, with captains, lieutenants, and sergeants. and privates, The participants in this ride dress in "period clothing" - fringed jackets, white dress shirts, and chinks (amputated chaps) - and they purport to be "keeping history alive."

Except, they really are not.

To begin with, Arizona never hosted a pony express. Mails in the territorial period were hauled from one place to another by buckboard wagon or, after railroad began crisscrossing the region, by train. The original pony express was a very short-lived phenomenon, lasting only 18 months, and running a direct course from St. Joseph, Missouri to Sacramento, California. The original Pony Express riders never came close to Arizona, as the territory was still Apacheria, and the riders (who did not carry weapons) probably would not have survived passing through it. The original Pony Express service was disbanded with the advent of the transcontinental telegraph lines.

Aside from this, there is the issue of the group's chosen name.

The "Hashknife" was the nickname given the Aztec Land and Cattle Company, which, in 1884, purchased a million acres along the Atlantic & Pacific railway line in northern Arizona, near Holbrook. The company, which was owned by investors from the east, proceeded to import cattle from Texas to fill the land. The Aztec company (or corporation, if you prefer) quickly became one of largest cattle interests in the territory. The nickname was derived from the pictographic brand the company burned into the hides of its cattle. Said brand somewhat resembled the tool used by line cooks of the era to chop potatoes. The Hashknife/Aztec Land and Cattle Company had nothing at all to do with the delivery of mails in the Arizona Territory, though some of the men the company employed – mostly hard-case cowboys out of Texas - did occasionally rob them

Which brings me to my next objection (and the most ironic) to the idea this is some kind of historical production. The real Hashknife cowboys were a wild and wooly bunch of young men, and a number of them were outright criminals. Among the men who rode for the Hashknife at one time or another were the outlaws “Red” McNeil and “Kid” Swingle, the murderer Parker Fleming, all four of the Canyon Diablo train robbers, and a number of men who fought with the Grahams in the Pleasant Valley Feud, including the notorious Blevins brothers. Frazier Hunt called the Hashknife cowboys “thievinist, fightinest bunch of cowboys” in the territory. The historical record bears this declaration out.

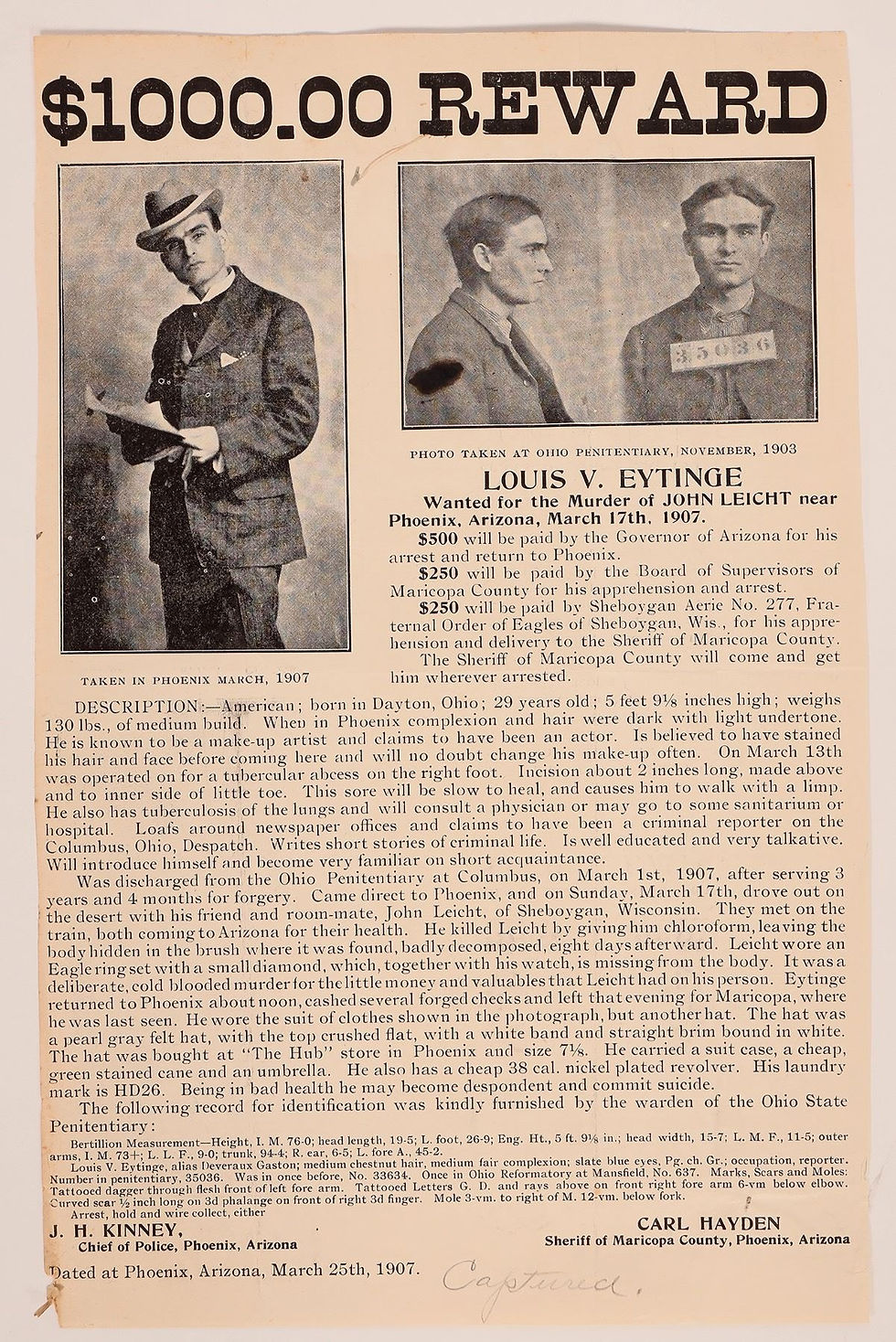

Most the original Hashknife cowboys were far from affluent. They were youthful (most cowboys of the era were under 35-years-of-age), underpaid, overworked, iterant laborers, with little education and few marketable skills. They were fortunate if they owned a single “go-to-meeting” shirt, a working firearm, and the horse which they rode. Quite the contrast with these older, propertied, gentlemen, with law enforcement and military backgrounds, and adequate monetary assets, who comprise the Hashknife Posse of today. Also, the Hashknife cowboys of yore did not wear chinks or fringed jackets (see accompanying photograph).

As a historian and author, I take exception to the assertion that the modern Hashknife Posse is “keeping history alive.” There is nothing at all historical about this annual event. Much like the various Old West reenactment groups which are ubiquitous in this state, the Hashknife Posse if providing an entertainment package (while flaunting their privilege and prosperity), not a historical program. Not that this is anything new. “Buffalo Bill” Cody did exactly the same thing. He took the rough-and-tumble cowboy (basically, a man who was an indigent, migratory laborer), sanitized and homogenized his rather dubious image, and created a near-mythic legend, which is, even today, recognizable worldwide. Like the Hashknife Posse, Cody insisted his "Wild West Congress" was not an entertainment spectacle, but a serious historical program. In truth, Cody’s shows were pure pageantry, just as the Hashknife ride is.

Reining in my extremely cynical disposition for a brief moment, I will grant it is possible (unlikely, but possible) this Hashknife Pony Express show could pique the curiosity of some young person in the audience about the history of this great state. This young person might even decide to research this history for themselves. Of course, this young person will find out very quickly, as did I, the real west had very little in common with the mythical west, as presented by groups like the Hashknife Pony Express. Hopefully, this will not deter saif young person (who probably only exists in my imagination)

from further study of this grand period in history.

Comments